When an Art Exhibition Opens in Covid Times

by Gayle Clemans, Cornish Art faculty

When an Art Exhibition Opens in Covid Times

During these times of Covid-19, our perceptions of time and space are heightened and skewed. Standing masked and six-feet apart or gazing at grids in digital breakout rooms, we say things like, “unprecedented,” “this is historic,” and “what day is it?”

When and where we experience art is also in question. With museums closed and funding diminished, art is viewed and created differently. The precarity of being an artist has been exacerbated. The ability to see art in the flesh is restricted. And yet the soul-healing, consciousness-raising, world-revealing benefits of art are deeply felt and widely proclaimed.

Now, almost one year into the world’s struggle with this pandemic, an art exhibition has opened, displaced in space and time, and historic in more ways than one. It is the postponed BFA show for artists who graduated from Cornish College of the Arts (Seattle, WA) more than six months ago. They are part of the class of 2020, the first to graduate during this public health crisis.

Now, almost one year into the world’s struggle with this pandemic, an art exhibition has opened, displaced in space and time, and historic in more ways than one. It is the postponed BFA show for artists who graduated from Cornish College of the Arts (Seattle, WA) more than six months ago. They are part of the class of 2020, the first to graduate during this public health crisis.

It is also the first exhibition in the 9th Avenue Gallery, the beautifully revamped street level of the historic Beebe Furniture building (built 1910), now part of Cornish’s South Lake Union campus. The big space is filled with light and grounded by old wooden floors and exposed ductwork. You can peek in through the large windows, but with renewed restrictions on indoor gatherings, most people – including many of the artists themselves – will only experience the exhibition online.

With careful documentation, a virtual walkthrough, and social media sharing, it may live longer and more expansively than previous exhibitions. In some ways, art is more accessible than ever before.

But these artists didn’t intend for their culminating show be a test case for how art responds to a global pandemic. They didn’t choose to be swept up in these twists and turns of time and space.

Their work speaks of their own worlds, different worlds, creative discoveries, revealed struggles, and stories.

Cornish Art Graduates

Colby Bishop’s abstract soft sculptures cuddle intimately with each other or hang limply from metal armatures. The brightly-hued, polymorphous forms have their own personas, like uncanny beings who exude a sweet eroticism or a deep desire for connection and support.

The paintings and mixed-media sculptures by Katie Currier contain grids and color and humor and handiwork in ways that are seriously formal and insistently irreverent. They call back to post-minimalist organic abstraction while expanding those boundaries to embrace craftwork and domestic structures like vaguely organic floor plans and snippets of fences. This is dexterous stuff.

The organic-yet-fabricated sculptural installation by Michaela Elias seems to grow out of its soil base. Cylindrical metal armatures are sheathed in gorgeously imperfect hand-made paper that hovers on deterioration, as if it’s about to slough off. Other work by Elias – large, colorful wall pieces of tied and pieced-together textiles – support these impressions of powerful growth and purposeful decomposition.

The tall, narrow paintings by Nate Haskins are like windows into a psychic world of deep emotion and import. Abstract vertical figures of black and dark yellow gather in dense groupings and fluidly interact with shadowy backgrounds. In tandem with this intensity of tone and composition, there is also a searching, lingering sensation, a feeling of expectation.

Holly Jones creates prints that lure you in with mottled textures and rich colors, along with enticing hints of phrases and blocky letters that are scrambled, camouflaged, or sliced out of the paper. Everything about these works wants you to come closer, get intimate, and decipher the sentiments which are tantalizing but a little untrustworthy: “You Next to Me,” “It Lasts as Long as We Let It,” “Fool Me Three Times.”

Germain Mitacc’s paintings reveal journeys inward toward the self and outward, out from and across the canvas. The complex constructions of repeated shape and line, might seem, in other hands, like painstaking exercises in cerebral abstraction. But there are hints of psychedelia, soft or analogous color palettes, and a sensitive push and pull of depth and surface, all of which reverberate with emotional and psychological implication.

The installation from Jae Muñoz can be approached as a whole: a soothing home altar that gathers warm-toned paintings and small objects. Moving closer, each element discloses more opportunities to seek, reflect, and possibly heal. The paintings are structured-yet-surreal, with gentle geometric facets surrounding realistic vignettes: animals, flowers, the artist’s self-portrait. The paintings themselves lie on top of, or are topped by, personal photographs. There are profound fragments, questions, and histories to ponder here.

Charlie O’s work revolves around sprawling, falling, typically male, almost archetypal bodies. Large, vivid paintings of bodies that fall amidst cityscapes or abstracted landscapes hang on the walls surrounding a video-sculptural installation. Figurines in white, metallics, or camo-green stand against, or collapse on top of, monitors which glow with spiraling footage shot from a drone. The effect is a repeated, scaffolded, dizzying examination of normative bodies and patriarchal structures.

Mo Quick’s cartoonish images are lively and strange. While infinitely delightful to look at, there is dark mischief afoot. Wild-eyed animals, alarmed stars, and impish humans populate Quick’s woodblock prints, a grainy form that lends a vintage flair. We are left wondering, perhaps even worried, about what is happening in these wondrous illustrations, each of which feels like a mysterious excerpt from a short story.

Squire Simpson draws, paints, and creates prints of fantastical cityscapes, expansive in scope and intricate in detail. But there is also a familiar loneliness to sites, with their stark towers clustered in futuristic, enigmatic, even threatening settings. The viewer hovers just outside these scenes, as if ours is the only gaze in these speculative worlds.

Sanoe Stevenson-Egeland’s deft skills with realism, painting, and print-making might suggest imagery and meanings that are easy to read. They are not. In fact, the complex compositions, shifting perspectives, and luminous color schemes seem to expose the ways we re-present or recall scenes, events, or memories. In these works, and in our minds, we can build narratives that have complicated relationships with reality and truth.

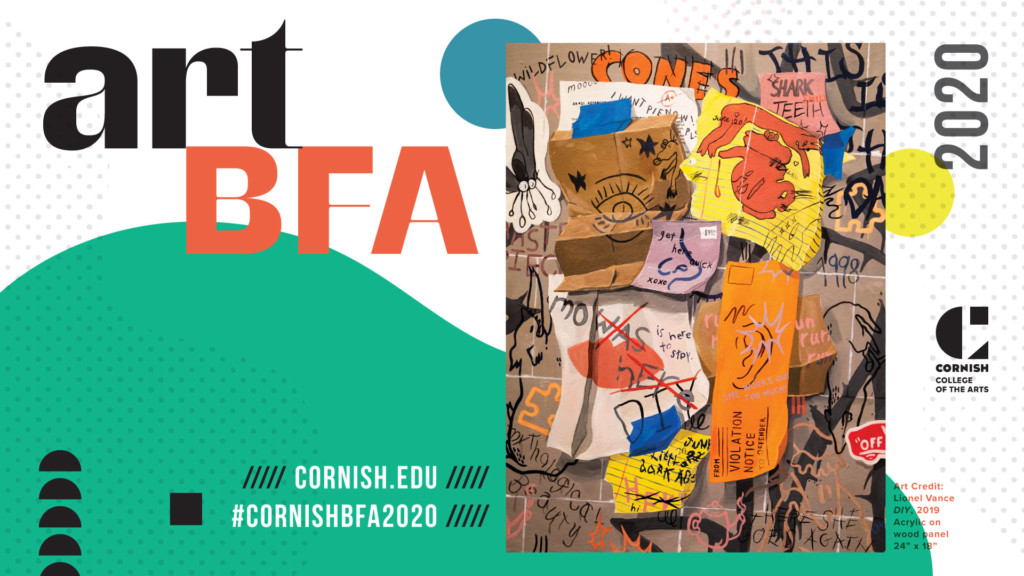

Lionel Vance’s realistic renderings of commonplace realities are so captivating that the more cryptic implications can sneak up on us. The detailed paintings of graffitied walls and messy bedroom floors function as still lifes of domestic or personal spaces. And just like art historical still lifes, deeper meanings are at play. Vance paints scraps of mementos, words, clothing, and spaces to compose intimate portraits of loved ones or complex portrayals of memory.

2020 Through Lenses of Change and Isolation

As much as each artist quests toward their own insights, formal encounters, or social narratives, their work may inevitably be interpreted through the 2020 lenses of change and isolation. Yearning, tension, risk, and revelation – these sensations permeate the show along with visual and metaphorical boundaries, connections, networks, slippages, and fragments.

Their collective statement was written back in the spring of 2020, after a whirlwind of closing up studios at Cornish, arranging home workspaces, and scrambling to locate resources and new networks of support, all while navigating increasingly dire health information, turbulent politics, and mounting demands for racial justice. In the statement, these artists write, “The work in this exhibition represents a number of triumphs and transformations…The improvised nature of adaptation has taken much of the work in new directions, and as we collectively learn and unlearn institutional structures in various respects, there is close reconsideration of the terms ‘finished’ and ‘finale.’”

The exhibition does function as a “finale” for these artists; it is a long-anticipated, dramatic closure to their time as students. But it was installed after their graduation and includes some work created after their time at Cornish. It provides a unique peek into life in the thick of, at the end of, and in the months following art school. We can see the emergence of potent and resilient individual practices. But it is also a group show, forged during a collective, global experience. The exhibition includes work created before and during the pandemic. There is no after. Yet.

There is nothing final about this exhibition.

—-

Essay by Gayle Clemans, writer, art historian, Associate Professor of Critical & Contextual Studies, Cornish College of the Arts, December 2020.

Art Credit: Lionel Vance | DIY, 2019 | Acrylic on wood panel | 24” x 18”