The History of a Photo

As we begin to celebrate Merce Cunningham’s centennial, we look back at the performance of the 3 Inventories of Casey Jones and the creative collaborations brewing in the Cornish Dance Department during Cunningham’s time as a student. (This blog was originally published in the spring of 2019.

The History of a Photo

by M Bocek

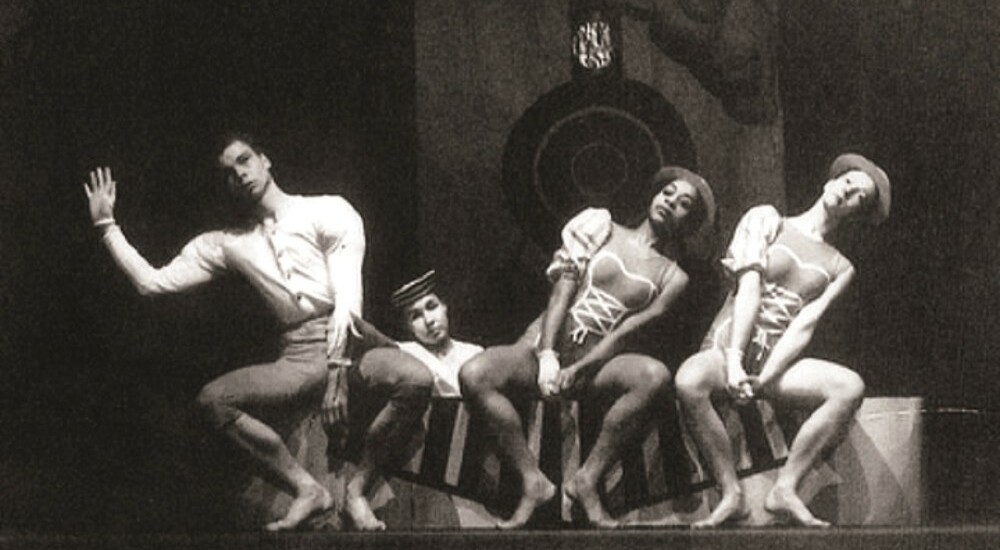

More than a half-century ago, Seattle photographer Phyllis Dearborn froze on black-and-white film a moment from a whimsical bit of choreography. There are four dancers in the shot, but our attention falls first on the familiar face of the young man with curly hair. Almost anyone connected with the college can tell you who it is: Merce Cunningham. Cunningham, as everyone knows, went on from Cornish to become one of the major figures of dance.

Called 3 Inventories of Casey Jones the piece was a fun romp—but the fun so brilliantly captured in the photo masked a very serious drama on the direction of dance and the school that was unfolding at Cornish just a few years before Nellie Cornish would leave the school that bore her name. At the center of the drama was the young head of the Dance Department, a product of the Cornish School and a favorite of Nelly Cornish. This dancer, choreographer, and educator would go on to great success, alumna Bonnie Bird ‘27-30.

In 1927, when Bird was 13, Caird Leslie folded his ballet school into the Cornish School and became head of Dance. It was the second go-round for Leslie at the Cornish School. By 1928 he was gone again and the future of ballet instruction was in question. Nellie called each dance student into her office to deliver the news personally that ballet was being deemphasized in favor of modern dance. “Modern” was still very much developing as a form

Ever strong-willed and rebellious, Bird organized an underground ballet class at Cornish in protest. This revolt was shrugged off by Nellie Cornish, it seems, who no doubt saw something of herself in Bird. “She was my mentor,” Bird said of Nellie, “and she bossed me around a lot. She also thought I was one of the most stubborn [sic] that she ever knew.” But the new head of Dance, Louise Soelberg ’26, slowly won her over to modern. At a time when everyone in the world was trying just to define what modern dance was, Soelberg was teaching the newer form by teaching ballet alongside it

After taking classes with Martha Graham in Cornish’s summer courses, Bird left for New York with Nellie’s blessing to study with Graham. It was a start of a long and fruitful relationship with Martha Graham, first as student and ward, then as a dancer in her company, the Graham Group. Later, her can-do attitude made her a trusted assistant and led at last to her certification as a teacher of Graham technique.

After five years of intense work and touring with Graham, Bird felt ready to strike out on her own. Her new opportunity came exactly where she had bloomed as a student. Nellie Cornish hired her in the spring of 1937 as the new head of her school’s Dance Department.

Cornish and “Bonnie Bird and Group”

Bird was excited at the prospect of returning home to Cornish. She was just 23 years old. Her return to the Northwest had included a highly successful summer workshop at the University of Washington. Building on this, she had suggested to Nellie Cornish that she could be advertised as the only certified teacher of Graham Technique on the West Coast.

But Nellie was so distracted by other battles at the school that she didn’t advertise the classes at all. When Bonnie Bird arrived for the fall term, she was crushed to find this out and the result: she would have just a handful of students.

Faced with the disappointment of the limited enrollment, Bird decided to look at the diminutive size of the department as “not a flaw, but a feature.” She poured her considerable creative energy into forging a unique learning environment for her students and her school. By May 6, 1938, when Bird and her dancers took part in a fundraiser to support the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War, they had an identity. They appeared as “Bonnie Bird and Group” – elsewhere billed as “Bonnie Bird and her Dance Group.” It is evident that Bird thought of her collection of students and teachers as a production unit.

Luckily, two of Bird’s small contingent of dance students were quite good: Dorothy Herrmann and Syvilla Fort, both shown in photo above. The two were in almost all the photos of “Bonnie Bird and Group.”

While not the first African American student at Cornish, Fort would go on in dance to become one of the most famous. For years she had been solo-tutored in dance, as no ballet school in Seattle would accept an African American dancer. Generous even as a girl, Fort turned around and organized dance classes for the smaller children in her neighborhood to pass on what she learned, an experience which presaged her later fame as a teacher in New York. But where other schools said no to Fort, Cornish said yes. Fort stayed at Cornish for five years, completing the dance course.

Merce Cunningham Recruited

Bird’s first order of business was to attract more students. Due in large part to the open structure of the school under Nellie Cornish, theater students were required to take dance. Bird was especially taken with a lanky young man named Mercier Cunningham. Cunningham, “Merce” to his friends, had taken a good deal of dance in his younger years in small-town Centralia, Wash. He was not thriving in his drama classes, and Bird offered him a chance to express himself in a way that bridged drama and dance. Bird could see something special in him, even then. “Even though he was still raw,” Bird told biographer Bell-Kanner, “he had a magical quality that wowed people.”

It was not long before Cunningham transferred to the Dance Department.

John Cage Arrives

John Cage is not in the photograph but he was very much part of the “Bonnie Bird Group” at this time. During the summer of 1938, while with Graham at the Mills/Bennington workshop in Oakland, Bird had been on the prowl for someone to replace composer Ralph Gilbert (earlier poached from Cornish by Graham). Bird was introduced to a young composer who had studied with Schoenberg. Cage warned her that he was an experimentalist, and Bonnie assured him that she was, too.

Cage had been engaged as an accompanist, but also as a composer for dance, just as Gilbert had been. Soon after arriving at Cornish, he also became a member of the faculty teaching a class in composition.

From all indications, Bonnie Bird led her department in a very free and exciting exploration of dance, theater, and music. In 1938, Casey Jones came to the stage of the Cornish Theater (now called PONCHO at Kerry Hall). Bird choreographed and possibly designed the costumes, John Cage organized the music composed by Ray Green, and Xenia Cage, John’s wife, designed the set. The whole piece was set to percussion music, Cage’s most recent obsession. Cage would go on to start one of the first percussion orchestras ever at Cornish, made up of himself, Xenia, some actors, dancers, and a music student. The instruments were whatever was at hand or could be fabricated. The group toured the West Coast. Later, more music students were added to the group.

Cunningham, Cage, And The Rest Move On

During the summer of 1939, Bird took Cunningham and Herrmann to Mills with her to work with Martha Graham. As she had done with Bird herself, Graham invited both to begin training with her company. Herrmann had fallen in love and declined. Cunningham, on the other hand, eagerly accepted the invitation to go to New York, departing a year short of completing his Cornish degree.

For Bird it was a disaster; the department was paper thin as it was without losing a dancer like Cunningham. Her worries extended to Cage and what plans, if any, were in the works for him as the School prepared for life without Nellie Cornish.

“John Cage is giving a concert next Thursday at Mills College,” wrote Bird to the assistant head of school on July 29 of that year. “The people here are very impressed with him. I think it would be unwise for Cornish to lose him – I would advise writing to him – he is restless because of the school’s indecisiveness [illegible words] to reach a conclusion.”

But the spring term of 1940 began without Nellie Cornish. By February and March, the acting director informed John Cage that his contract would not be renewed and Bird that she would no longer be head of the Dance department. Cage’s firing and Bird’s demotion were part of a general restructuring of Nellie’s faculty and curriculum.

As the academic year ended, so had an era. The people in the picture, and just outside of the view, scattered. Bird started a new school in the U District. Hermann married. Cunningham danced with Graham in New York. Cage and his wife departed for the New Bauhaus in Chicago. Fort left Seattle for Los Angeles, where she would dance with the Katherine Dunham Company. Later she would teach the Dunham technique in New York.

Phyllis Dearborn’s photograph of the Bonnie Bird Company captures a singular moment of collaboration for Cornish and, indeed, for arts education and dance history.

A longer version of this article was published in February 2016 in The Cornish Magazine. This article has been edited to fit the web format.

Photo: Phyllis Dearborn. “3 Inventories of Casey Jones” [l to r] Merce Cunningham, Bonnie Bird, Syvilla Fort, and Dorothy Herrmann.